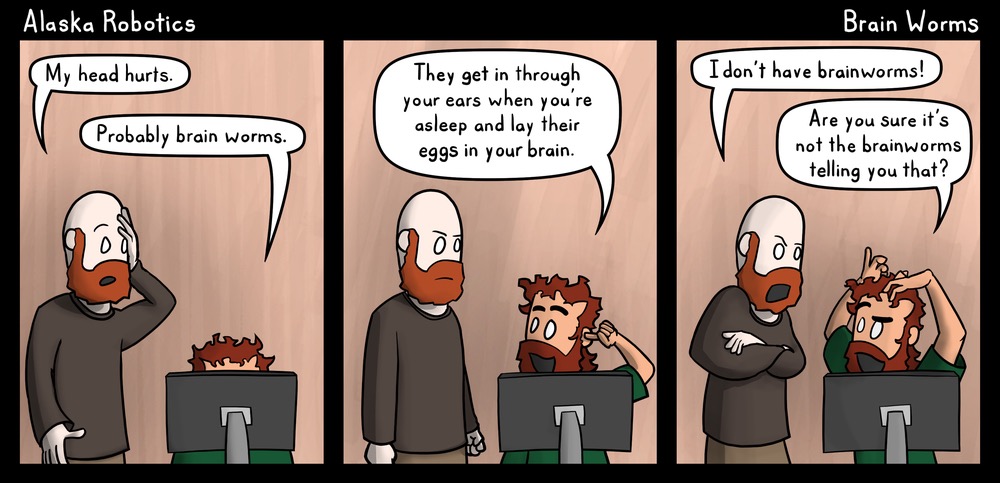

As I mentioned during The Film Board’s review of You’re Next, I have just recently watched Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color. After watching it I felt like my brain had been hacked by Malickian brain worms. It’s a film where music, sound, and images combine to touch the deeper parts of the mind. It was a feeling I hadn’t had since watching The Tree of Life.

This is your brain after Upstream Color.

There are some filmmakers, like Carruth and Malick, that can disorient their audience yet still keep them engaged and focused throughout the film. Why can a film that is putting intentional barriers before the audience be more engaging than one that attempts to be easily accessible to the audience?

I am reluctant to admit that I have endured Aeon Flux and Ultraviolet. Both are stories that are easy to understand, but neither kept my attention because they are the most boring action films I have ever seen. I didn’t have to work, or think much, and should have had an enjoyable experience. But I didn’t.

My viewing experience with Upstream Color was completely different. It should have been easy to be bored with this due to minimal dialogue, multiple story lines, and no effort to explain why these events are occurring. Yet I was intently focusing on the dialogue and the images to attempt to piece together how these characters are connecting to each other. I did a lot of work, which could have been a reason to turn it off. Instead, I found myself ruminating on my experience with the film and eager to give it a second viewing.

Why do we love movies that make us work so hard?

Maps help us make meaning.

The map, please.

I’ve always believed that you can either tell a complex story simply, or tell a simple story complexly. Some of the most critically acclaimed films have relied on the a simple story and complex structure as the method for story telling. Perhaps one the most commercially popular and successful is Pulp Fiction, the film that brought non-linear storytelling to mainstream audiences.

The films 21 Grams spends about the first 15 minutes introducing the three main characters, but not in any chronological order. What we do get is a sense of who they are and what their personal stories are. It’s not until later that we begin to see how their stories are interconnected with each other.

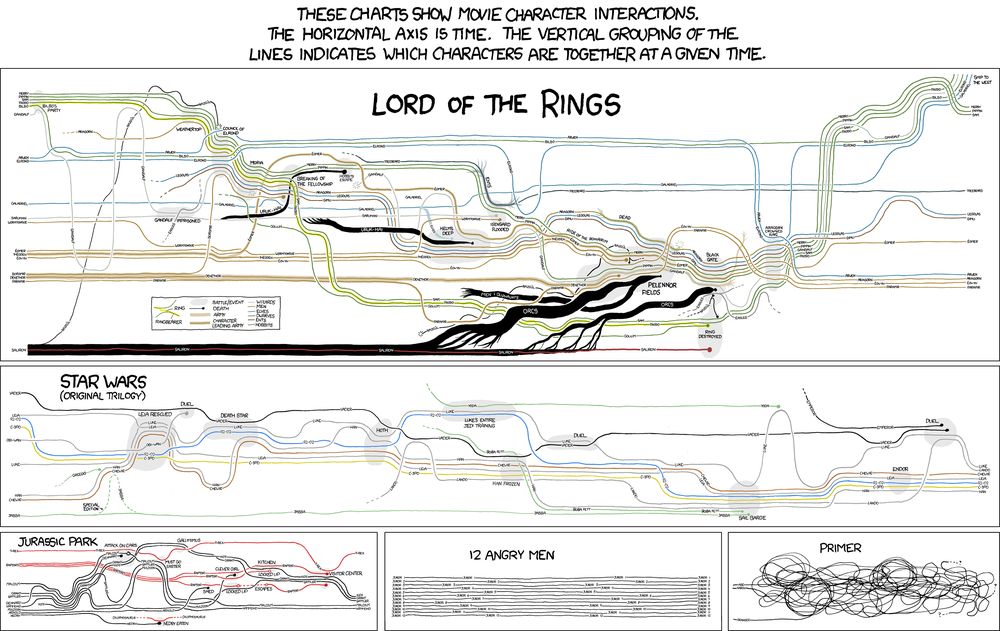

Films like these often result in fan-generated maps to help us piece together the events into a more familiar sequence of cause then effect, or beginning to end.

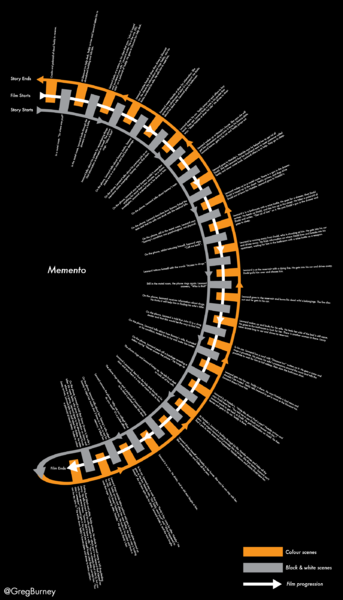

With Memento, Christopher Nolan played around with the idea of the beginning and ending of a story by telling the story from the end to beginning, and wove in another story that may actually be the other half of Leonard’s story.

Memento in a linear sequence from “start” to “finish”.

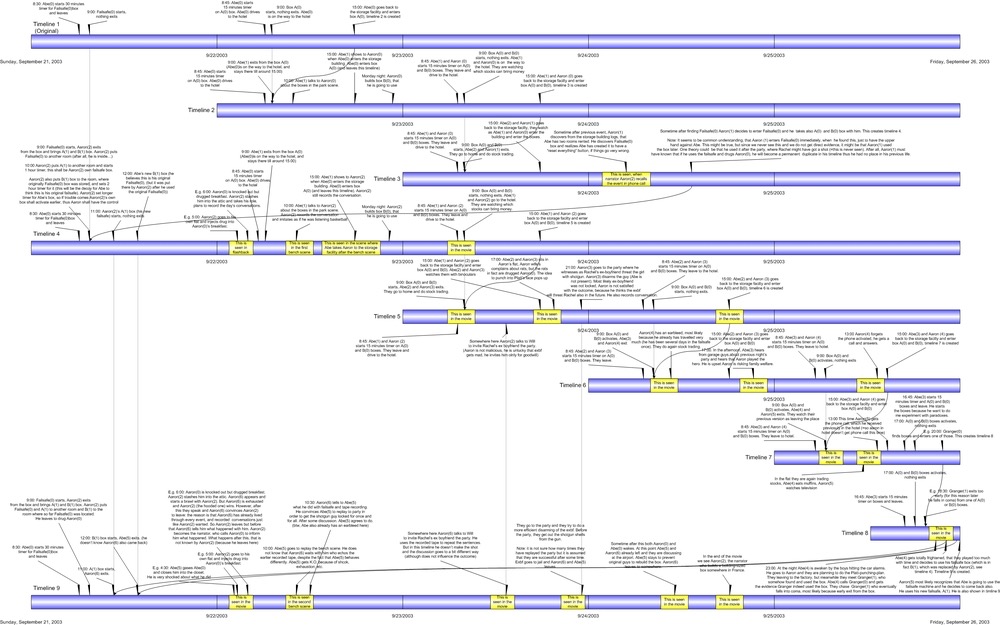

Primer is a film that requires more than one viewing to even begin starting to understand the multiple timelines. Yet, despite the amount of work that these films require from their viewers that have received critical praise and devoted fans. These are puzzles that we love to return to and discover different facets to our own personal experience with them.

It only takes 77 minutes to watch it once, but you need to see it 77 times to unravel everything that happens.

Where is my mind?

Then there are those films where the audience must work to assemble meaning from the actions of the characters to understand the logic of the world we are presented with. In these stories common sense and logical responses are undermined through repetition and unconventional continuity, to create an experience that is not consistent with our understanding of the world. We are presented with a foreign formula that, which as we begin to build understanding of the internal consistency of the world, requires us to step away from our own assumptions and expectations of how reality functions and embrace this new world.

Films like The Machinist, Donnie Darko, and Upstream Color take place in a world that is similar enough to our own world to feel familiar, yet display differences that require our close attention. If we don’t pay attention to these differences we loose the ability to understand the journey we are on.

The Machinist, most remembered for Christian Bale’s extreme weight loss, is a slow trip into the darker side of guilt. It’s a challenging film to watch, but I was surprised at the payoff. What I thought was a film trying to be clever and mysterious for its own sake turned into an interesting tale of morality.

As for Donnie Darko …

Watching a movie with a rabbit named Frank is only the start of your troubles.

These demands on the audience, can either alienate the viewer or, as the result of carefully constructed craftsmanship, result in a unique filmgoing experience. Some may argue that the payoff is not worth the amount of work required.

I, for one, welcome the Malickian Brain Worms and the transformative power of challenging films.

Don’t let the brainworms get you down.